The Destiny of Nineveh

- Ryan Moorhen

- Jan 15, 2020

- 4 min read

Nineveh (Akkadian: URUNI.NU.A Ninua) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located on the eastern bank of the Tigris River on the outskirts of Mosul in modern-day northern Iraq. Today it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris and the Nineveh Governorate takes its name from it.

The area it occupied was originally settled as early as 6000 BC during the late Neolithic period. Deep sounding at Nineveh uncovered soil layers that have been dated to early in the era of the Hassuna archaeological culture.

By 3000 BC, the area had become an important religious center for the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar. The early city (and subsequent buildings) was constructed on a fault line and, consequently, suffered damage from a number of earthquakes. One such event destroyed the first temple of Ishtar, which was rebuilt in 2260 BC by the Akkadian king Manishtushu. It was the capital of the Assyrian Empire.

It was one of the oldest and greatest cities in antiquity. It was the largest city in the world for approximately fifty years until the year 612 BC when, after a bitter period of civil war in Assyria, it was sacked by a coalition of its former subject peoples, the Babylonians, Medes, Chaldeans, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians.

In the Hebrew Bible, Nineveh is first mentioned in Genesis 10:11: “Ashur left that land, and built Nineveh”. Some modern English translations interpret “Ashur” in the Hebrew of this verse as the country “Assyria” rather than a person, thus making Nimrod, rather than Ashur, the founder of Nineveh. Sir Walter Raleigh’s notion that Nimrod built Nineveh, and the cities in Genesis 10:11–12, has also been refuted by scholars.

The discovery of the fifteen Jubilees texts found amongst the Dead Sea Scrolls, has since shown that, according to the Jewish sects of Qumran, Genesis 10:11 affirms the apportionment of Nineveh to Ashur. The attribution of Nineveh to Ashur is also supported by the Greek Septuagint, King James Bible, Geneva Bible, and by Historian Flavius Josephus in his Antiquites of the Jews (Antiquities, i, vi, 4).

Nineveh was the flourishing capital of the Assyrian Empire and was the home of King Sennacherib, King of Assyria, during the Biblical reign of King Hezekiah and the lifetime of Judean prophet Isaiah. As recorded in Hebrew scripture, Nineveh was also the place where Sennacherib died at the hands of his two sons, who then fled to the vassal land of Urartu.

It was the Assyrian king Sennacherib who made Nineveh a truly magnificent city (c. 700 BC). The enclosed area had more than 100,000 inhabitants (maybe closer to 150,000), about twice as many as Babylon at the time, placing it among the largest settlements worldwide.

At this time, the total area of Nineveh comprised about 7 square kilometres (1,730 acres), and fifteen great gates penetrated its walls. An elaborate system of eighteen canals brought water from the hills to Nineveh, and several sections of a magnificently constructed aqueduct erected by Sennacherib were discovered at Jerwan, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) distant.

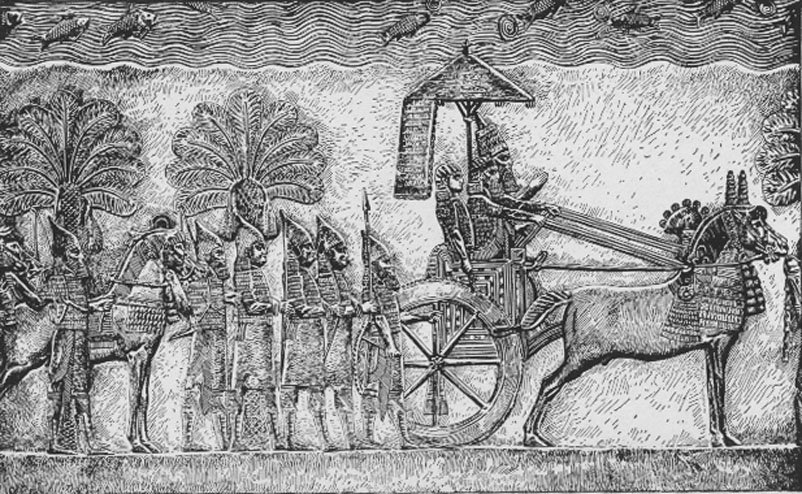

He laid out new streets and squares and built within it the South West Palace, or “palace without a rival”, the plan of which has been mostly recovered and has overall dimensions of about 503 by 242 metres (1,650 ft × 794 ft). It comprised at least 80 rooms, many of which were lined with sculpture.

The canalization network built by Sennacherib to bring water to Nineveh and the surrounding territory in around 700 BC is perhaps the most significant example of monumental cultural heritage in northern Iraqi. It is possible that the garden which Sennacherib built next to his palace, with its associated irrigation works, was the original Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Canals, imposing stone aqueducts, rock reliefs and commemorative inscriptions are scattered over a territory covering almost three thousand square km in the Duhok region, but they all belong to the same impressive undertaking.

The first volume of the Italian Archaeological Mission to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (IAMKRI) series is entirely devoted to the recording, conservation, protection and enhancement of Sennacherib’s irrigation system and the presentation of the project for the creation of a related archaeological and environmental park.

The book focuses on the two most important sites of Khinis and Jerwan, which represent the core of the park project, but preserves the general unity of the Assyrian system of canals and rock reliefs by including also the reliefs of Maltai and Shiru Malikhta. Modern multimedia technologies will allow all the sites to be managed and visualized both in their specific locations and in relation to the entire complex.

The abundant architectural documentation gathered in the field together with the management plan of the Assyrian monuments and the recognition of their outstanding universal value have led to the drafting of a proposal for their inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List. This will enable the better protection of this unique complex and the wider local and international dissemination of public awareness of it.

The book of the prophet Nahum is almost exclusively taken up with prophetic denunciations against Nineveh. Its ruin and utter desolation are foretold. Its end was strange, sudden, and tragic.

According to the Bible, it was God’s doing, His judgment on Assyria’s pride (Isaiah 10:5–19). In fulfillment of prophecy, God made “an utter end of the place”. It became a “desolation”. The prophet Zephaniah also predicts its destruction along with the fall of the empire of which it was the capital. Nineveh is also the setting of the Book of Tobit.

Its ruins are across the river from the modern-day major city of Mosul, in Iraq’s Nineveh Governorate. The two main tells, or mound-ruins, within the walls are Kouyunjik (Kuyuncuk), the Northern Palace, and Tell Nabī Yūnus.

Large amounts of Assyrian sculpture and other artifacts have been excavated and are now located in museums around the world. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) occupied the site during the mid-2010s, during which time they bulldozed several of the monuments there and caused considerable damage to the others. Iraqi forces recaptured the area in January 2017.

Comments